It’s 0500 on a rainy Winter Monday morning in 1998 and I’m sitting in my car in the clinic parking lot at the Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, WA. I’m waiting to board the van that will be driving me, the Commanding Officer Captain Jon Berude, Command Master Chief Kathy Morrison, and my training partner LCDR Monica Berninghaus, whom I refer to as Dr. B. on a two-hour journey to NAS Whidbey Island. The two of us will be providing annual Navy Rights & Responsibilities (NRR) for the staff there.

NRR is an annual snoozefest that gives an overview of the Rights you have as a Navy sailor (very few) and of course Responsibilities (of which you had legion, including much of which you didn’t know you had until you screwed up and got your ass chewed).

Just 10 months earlier, I made my decision to leave the Navy at the 15-year mark and begin a new career as a management trainer and consultant. Since doing training was something I enjoyed and knew I’d be doing for the foreseeable future, I volunteered to be part of the Command Training Team (CCT). Which meant of course I had the joy of facilitating NRR.

The training was done with one officer and one enlisted person. I guess the officers needed someone like them to relate to while the enlisted monkeys got one of their own, me. Dr. B’s portion was about the Navy contract which was a bunch of words crammed onto way too many PowerPoint slides. It was boring stuff, and I was glad I would be teaching sexual harassment prevention and the Navy’s Core Values. Because the Navy had effectively put sexual harassment on the map at the 1991 Tailhook convention, it was only fitting they elevated this topic.

Since training was what I wanted to do for a living, I devoted myself to creating the ultimate NRR experience. Lots of stories and examples. I joined the ASTD (now the ATD) and read just about everything I could on facilitation. I was also teaching college courses at night so being in front of a crowd didn’t faze me.

So, as I’m sitting in the van waiting for Dr. B., I’m mentally going through my presentation slide by slide. But I’m not reading slides to this audience. I’m interpreting them, with stories, metaphors, and examples. I’m as ready as I’m going to get so I decide to try and take a little nap.

About the time, the Director for Administration LCDR Matthews drives up and informs us that Dr. B. had a family issue come up on Sunday and had to head out on emergency leave.

It’s too late to pull the plug on this event now. Kathy Morrison (who loathes me by the way) says, “It’s OK, Petty Officer Munro can do the entire presentation.” She hands me a copy of Dr. B.’s slide deck and now I have two hours to figure out how to teach this mess.

The ride to Whidbey Island takes you across the Hood Canal Bridge to the Port Townsend Ferry. This is the area where An Officer and a Gentleman was filmed. In fact, the little cheap motel where Sid Worley “celebrates” his girlfriend dumping him is just down the road. Then you drive onto the ferry for the rest of the journey.

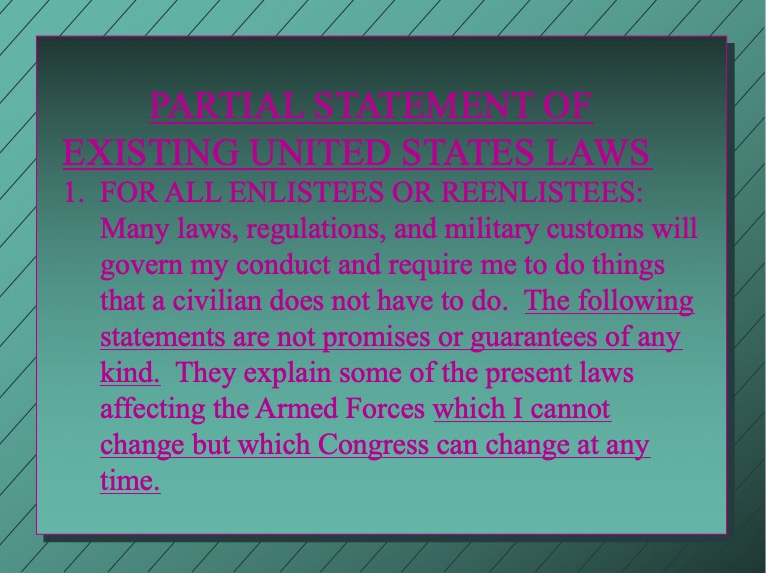

This is an actual slide from that presentation. I still have an old copy of it! Notice the wonderful color schemes! I didn’t create this obviously!

The slide deck in my lap looks like Greek. Way too many words stuffed onto a slide. I have no clue what it means so I simply write down the core message of the slide and try to figure out how to communicate just that. My plan is to say, “you can read this for yourself, but let me summarize the main thing for you.”

We are nearly there and are running about 15 minutes late. I’m nervous, but it’s like the nerves I felt years ago before a high school football game. More adrenaline than fear. I barely have time to use the bathroom.

Then, I enter the side door to the auditorium. The entire staff of nearly 50 officers, enlisted people, and civilians are already seated, patiently waiting while staring at me. I haven’t set up my laptop or anything. The Commanding Officer makes a few remarks as I’m hastily untangling cords, booting up the laptop (which takes about 3 minutes), rigging up the Proxima Lightbook projector, and then it’s my show.

Dr. B’s material is up first.

“Just do it,” I say to myself as I launch into the slides.

And I remember nothing after that. Not even my section of the presentation. I don’t know whether it’s just another memory lost to time or if it happened so fast and there was so much turmoil in my head that I just went on autopilot.

Then, it was time for Q&A. Typically, nobody has any questions because A, they are too afraid to ask, or B, they just want to get the hell out of there.

Nobody had any questions.

Then of course Master Chief Morrison stirs the pot.

“I’m sure some of you have this question,” she says before selecting the most controversial topic and asks me a question about that.

She has no idea how quick I am on my feet, so I deftly answer it and move on. There are no further interruptions.

The crowd applauds, most likely to celebrate the end of this two-hour torture.

I don’t know how to feel. Honestly, I’m mentally exhausted.

I’m talking to some of my peers there at Whidbey and then, from the left, walks one of the crustiest, meanest looking Naval Officers at the Command. He was an old Navy Captain, of which there were many at Whidbey Island since that was a typical place for a “twilight tour” which preceded retirement.

He stops in front of me and with a completely expressionless face informs me:

“Petty Officer Munro,” he says in a gravelly voice, “In my 35 years in the Navy, that was the BEST NRR I’ve ever sat through.”

Then he walked away.

In that second, I knew that my new career choice would be the right one. That was the last piece of affirmation I needed. If I could take the shittiest, most boring training program known to man and make it “the best in 35 years,” then I knew I could do just about anything.

And over the past 25 years, I have. What looked like a disaster in the making that rainy morning turned into a very profound moment. A moment that grew my confidence enough to punch way above my weight when I first started out. An event that helped me say “yes” to projects I knew down deep inside I had no clue about but knew I could figure out.

I’ve learned that nothing prepares you for life more than just getting out there and trying new things. Putting yourself to the test proves you’re still alive and relevant. It worked wonders for me early in my career, and as I wind down this one and prepare for the next chapter, I’m working on something exciting. And absolutely terrifying.

But that’s all part of the fun, isn’t it?

What difficult thing have you been putting off? What if this thing is just a test to see if you’re ready for new success?

Just do it.